Going back to school that Monday was awful. Somehow that morning I forced myself to drive to class. It took every bit of strength to put aside the emotions of my new life and keep going. As I approached the halfway point in my commute, a tiny, newborn deer lay dead in the road. The image immediately consumed me with insurmountable pain and grief. I wanted to scream. I wanted to turn my car around and go home, climb into bed and never get back out. I was so angry, so upset and disgusted.

How could God let that happen? How could God let that happen to a tiny, defenseless creature? To die like that, the first day born? Why? What was the point of it? The point of anything? And of course, there was no answer. There was nothing. That poor creature lay dead and no one in the whole damn world would care. It was over as if it had never even happened. That’s how it all felt. My dad was dying, would die and no one in the world would give a shit. The world would drive on by.

For reasons I don’t know, I actually still went to school. The pain, as if I’d been hit by a car, was still vividly intact. Any time I saw someone laugh or smile, I was filled with hate.

My reaction, if anyone had recorded it, would have been my face recoiling in horror with pure malice as if they had stabbed me. Once I recognized this new feeling, I realized the whole semester was going to be hell. I tried to talk myself down, none of these people knew what I was going through. I needed to get a grip somehow, but it would be like that for a long time. Some days were easier than others.

I felt unbearable pain and resented every single person who was not feeling the same thing and going about their merry, little, normal lives. I was watching the living world with vengeance. This schism of balancing life and death was something I hadn’t prepared for. For years I had assumed, much like my dad, that he would “burn out” one day, not die slowly of a terrible disease. My family had not prepared on how to live with a long-term death sentence.

The weekend I found out about the cancer, my brain and body changed. Suddenly I couldn’t remember minute-to-minute things. I had to resort to millions of post-it notes, emails to myself, and an intricate planner littered with scribbled details. My brain became a sponge so over-saturated in pain, that it no longer could retain anything anymore. It was unbelievable. My once rigid and endless memories, both long and short term, had vanished into thin air.

•

Everyone was in denial. I definitely was. My parents were, in their own way. Not Jon. My sister tried to tell me that my parents claimed, a doctor hypothesized my dad could hang on for a year. I believed it, as my dad had wanted me to. Jon was cautious. He told me the statistics, he told me with great pain in his face. He could see my denial, in which maybe… “it wouldn’t be so bad.” He was weary; forced between telling me the aching truth about the death sentence of pancreatic cancer and letting me hang onto some fantasy of hope.

The days were long but school was a distraction. I felt awful about not being home. I even suggested coming home for fall break in October. My dad wouldn’t agree to it, saying there was nothing to be done. My mom talked with me on the phone and mentioned having to get new cups. She said something about my dad not drinking enough water. I said to get bigger cups, to fill up with more water. She scoffed and with a hushed voice said, “He wouldn’t be able to lift it.”

It was then, at that exact moment that I felt terrifying pain through my soul. I didn’t believe what she had said. I was too afraid to ask her to repeat it because then it might be true. That couldn’t be an accurate sentence. My dad was always physically strong. Her words left me terrified. A sinister shape of what was taking place in that house began to grow inside my mind.

I was worried about the strain that was going on in the house. My mom doesn’t know how to drive. The short answer and reason is trauma. She, much like my dad, came from a family of migrant workers. At the age of twelve, her parents, sister and three brothers were part of an accident involving migrants in the back of a truck traveling to the farm they were to work at. During the night the driver had fallen asleep and the truck flipped twice. Her father was the only one killed. In the aftermath of that tragedy, her mom had a broken collarbone and wore a brace for a year while doing many jobs to support her family. There were no counseling sessions at school for my mom. They didn’t even get to be at his funeral because they were all minors and stuck in a different state while my grandmother couldn’t move.

There would be no therapy to process the shock or her inevitable fear of driving. She attempted to learn a few times but it never materialized into anything long term. I don’t think her or my dad ever considered the situation to carry on forever, but it had. So in this situation, whatever shopping, doctor visits and other tasks were being done by my dad while he still could. They were also relying on favors from others.

•

During that semester and those months, I tried not to listen to music out of fear of permanent association with painful memories. But that was difficult, considering how much I love music and use it almost daily. Years earlier, one of my favorite bands had a message board and someone had posted a comment about their father dying. The commenter knew one of the band members had lost their father to cancer. They asked for his advice on getting through the experience. I recalled how alien it felt to read that question. How terrifying it was to even imagine something like that happening to me. Now that it was my reality, I thought about the advice he had shared with that grieving person.

I remember his specific words were, “Let it pass through you.” These words began to repeat in my mind. I tried to understand what he meant and how I would follow that advice? I figured it meant not to hold things in. That was easier said than done. Especially in a world that never stops, responsibilities don’t ever stop. No one wants to hear about your problems. Emotions are not part of being professional, nor is sadness the sparkling conversation starter that wins you friends when you’re ten years older than everyone on a college campus. There was no one for me to relate to. I had to figure out how to let the pain pass through me even with all the demands I had to answer daily.

Time went on and I was hopeful. I prepared myself for the fact that my dad may die within 9-10 months. I was stuck in school and there was no way out. The thought of capsizing my classes and burning all of my dad’s money away while he died made me want to crumble into dust. I couldn’t let him down under these circumstances. So I buried my head in work, it often felt dizzying but I didn’t stop.

With the approaching reality of going home in December, I began to lose hope. At some point I searched online for information about pancreatic cancer and found a blog. There were people talking about their experiences. I was looking for help, information and some encouragement, from someone who’d gone through it. I started to read one lady talking about her husband and she began with how he’d, “been gone for a year.” The horror and agony of those words crashed down on me like lightning. For a moment my vision blurred. It was the first moment thinking of my dad in the past tense. Rapidly, I closed the window as if it were a monster coming for me. I couldn’t see my denial.

•

During Thanksgiving, my mom was in hysteria. My dad was doing terribly. His medications and health were causing him to go in and out of consciousness, all day. She sounded terrified. She said he would be in his chair, eyes closed, moving his hands as if he were trying to cook. Her voice was angry and upset. I felt powerless on the other end of the phone line. Nothing I said mattered or helped, all I could do was listen. She was alone, going through this horrible thing. She sounded mad and honestly, anyone would be.

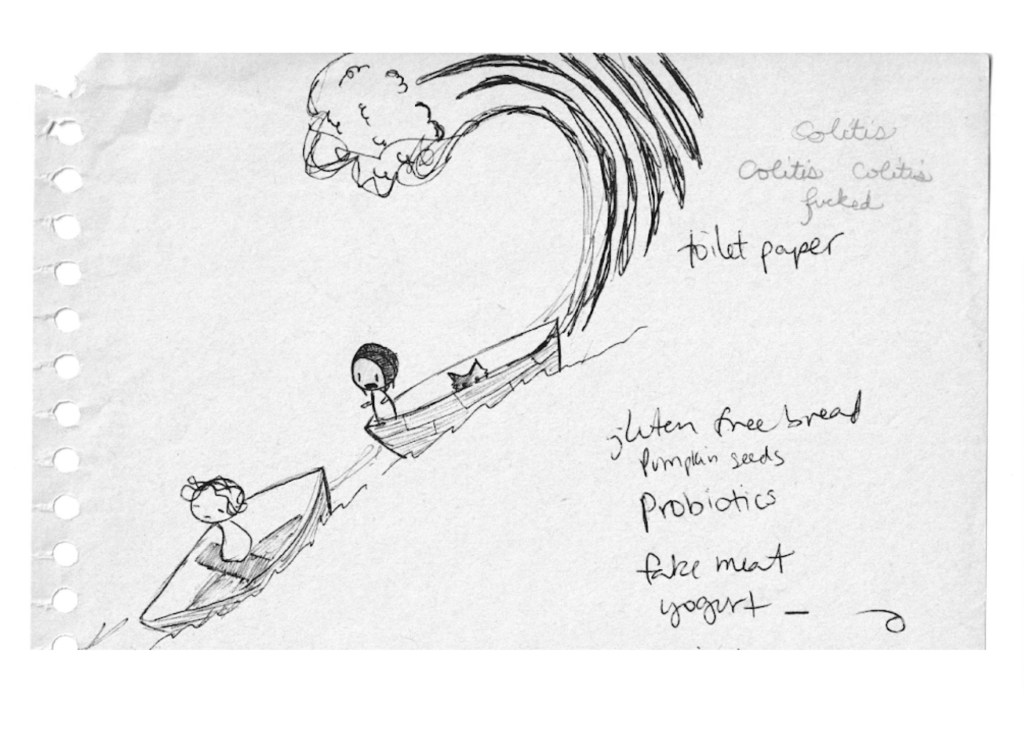

I remembered when my husband Jon was sick, years earlier. He became ill with what we thought was food poisoning, but after a few days he continued to worsen. The two of us were alone, with no health insurance. Weeks went by and I was terrified. Each day was terror and insanity. He refused to go to the doctor thinking it would get better, not wanting to rack up thousands of dollars in medical bills. He couldn’t eat, he just laid on the couch in pain. He wasn’t the person I’d known for years, it was like I was living with a stranger.

Normally, nothing ever bothered Jon. He never got sick, he was always kind, an exhaustingly patient and strong person. But in that state he was weakened, angry, distant and mute. Weeks went on and I tried to somehow function. People would call and I wanted to scream. I remember one time my mom called and she seemed so casual and lightly concerned. She didn’t understand, nobody did. Each moment was hell, everything was torture. I drew a picture of what it felt like.

In almost six weeks, Jon had lost twenty-five pounds. After several weeks he stood up and the bumps of his spine poked through his shirt. He took two trips to doctor’s offices and then to the ER, after I forced him to. It wasn’t until we scheduled an appointment with a G.I. doctor that we found out he had ulcerative colitis, something he found days earlier online through self-diagnosis. Days leading up to the procedure for a biopsy, we were hanging by threads. By the end of the debacle, we both looked shredded, slumped in our chairs. Jon looked much worse.

The day Jon came out of the hospital and they gave us the diagnosis, my dad was waiting intently at home by the phone for the results. I was still dazed and scared about his new diagnosis, something I’d never even heard of. When I called to tell him the news, I remember my dad being much more relieved than me saying, “Well someone else got the bad news today, but he didn’t.” As sad as I was, it jolted me. Until that moment, I hadn’t even considered the idea of a “worse.” Not only that, I realized how much my dad had been worried about us, about Jon, about us being faced with something far more serious than I could dare dream up. That’s the kind of person my dad was. Always knowing more than he let on.

Slowly, Jon got back to normal once he had medications, but I never forgot that experience and how it changed us. It was positively traumatizing. The absurdity of how humans constantly pretend things are okay, to not show weakness, to not appear dramatic, or be depressing and make other people feel uncomfortable. Jon and I had endured a month of pure isolated hell. I vividly remember how alone we felt, watching every other asshole on tv or at a store go on their merry way, full of normality while each second of our life was torture. And now here I was, calling my mom to ask her casually, calmly, about my dad. Now I was that asshole.

•

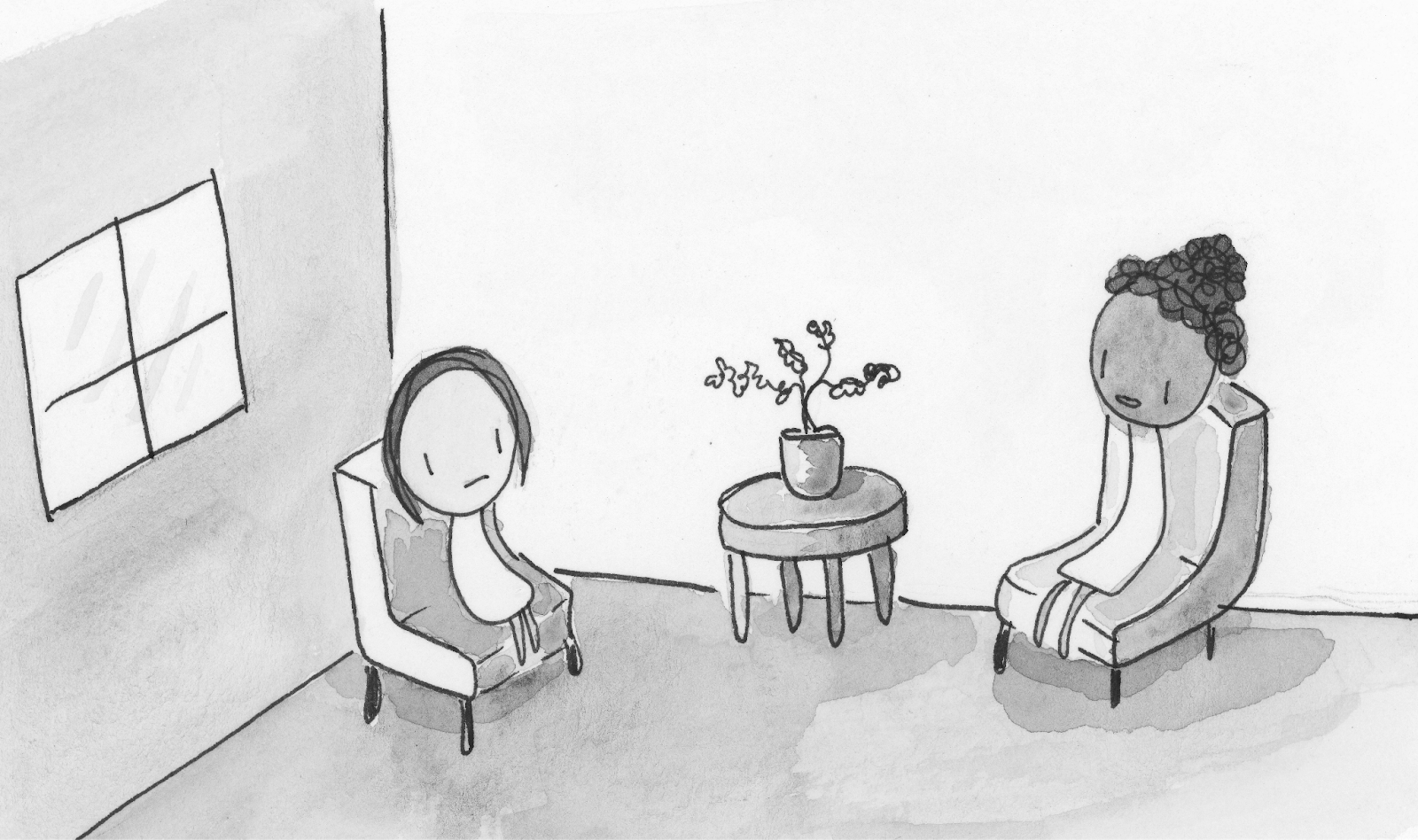

Fearing my return home, I decided I needed to talk to someone. Half the reason I went back to college for a second time was that I needed help with my life-altering anxiety. I knew that with tuition I was also guaranteed help mentally. My first year back I was fortunate to have had a counselor who helped end that misery but also helped me question a lifetime of irrational fears, self-sabotage and bad habits. I couldn’t help but to think how lucky I was to have made such progress mentally that year, just before proceeding into the worst stage of my life. There was absolutely no way I would have survived it without that counselor or those mental health services a year earlier.

Feeling clueless and powerless at this new situation I went back to the counseling center. My old counselor was now gone and I had to meet someone new, which is always a bad feeling because it’s like starting over. I agreed anyway, hoping for the best. This new counselor was a nice lady, from Cameroon. I remember I was initially unhappy when I left because she didn’t tell me what I wanted to hear. I was scared, more than words can say.

I wanted, needed, and desperately hoped that someone would tell me that everything was okay, that my dad would be okay. But instead, she cautiously said, “I don’t trust cancer,” I guess to mean, it can’t be planned for. She seemed to know before I did that my dad would die. It was a shock to hear someone be so bold that yes, things are dire, and you can’t control that.

She told me a story about her friend that had cancer and died. About how she never was upset in front of them in the hospital. That she would go to the bathroom and sob, clean up and go back to her friend and continue laughing and talking, “Maybe he knew, I don’t know.”

The counselor talked about how her dad had a stroke and died unexpectedly when she was younger. “I dream about him, meeting my baby,” she told me while smiling as if it were a happy memory. Ultimately, she made it clear that I was lucky to have time to talk with and be with him. “Be there for your dad. Enjoy your time with him, don’t be sad and cry, he is already sad, be strong for him.”

The thing that I walked away from that day was a painfully profound reality that it was not about me, at all. Whatever I felt paled in comparison to what my dad was going through physically, mentally, and emotionally. I decided my sadness was going to be on my own time. I had to be there for him and make the most of what we had.

December arrived and my dad’s birthday was coming up. At the school store, I bought a UCO hat to commemorate my pending graduation. The exhaustion of school had been a great distraction that I had even built the idea up that things might not be so bad. The semester was over and I believed that I would be finishing out my spring semester as planned with my happily anticipated graduation waiting in May.

I had done all my observation hours, tedious classes and studio projects with success. As a result, my right arm was so inflamed from the physical work of typing and metals-mithing that I literally couldn’t use it anymore. I had injured it so profoundly, it became a serious tennis elbow and carpal tunnel combination. This was my doing by following bad macho advice I’d heard my whole life to “power through the pain.”

Now I had both a wrist and elbow guard on daily to reduce what seemed to be permanent inflammation, hoping eventually it would go back to normal. Looking on the bright side, I at least had proved that counselor wrong. I had straight A’s and even made the President’s List. All three years I had put into that degree, all the hard work… how could it be that my dad wouldn’t even get to see me finish now? Going home, everything I worked for, now seemed almost meaningless. All I had to show for it was my wrecked arm.

•

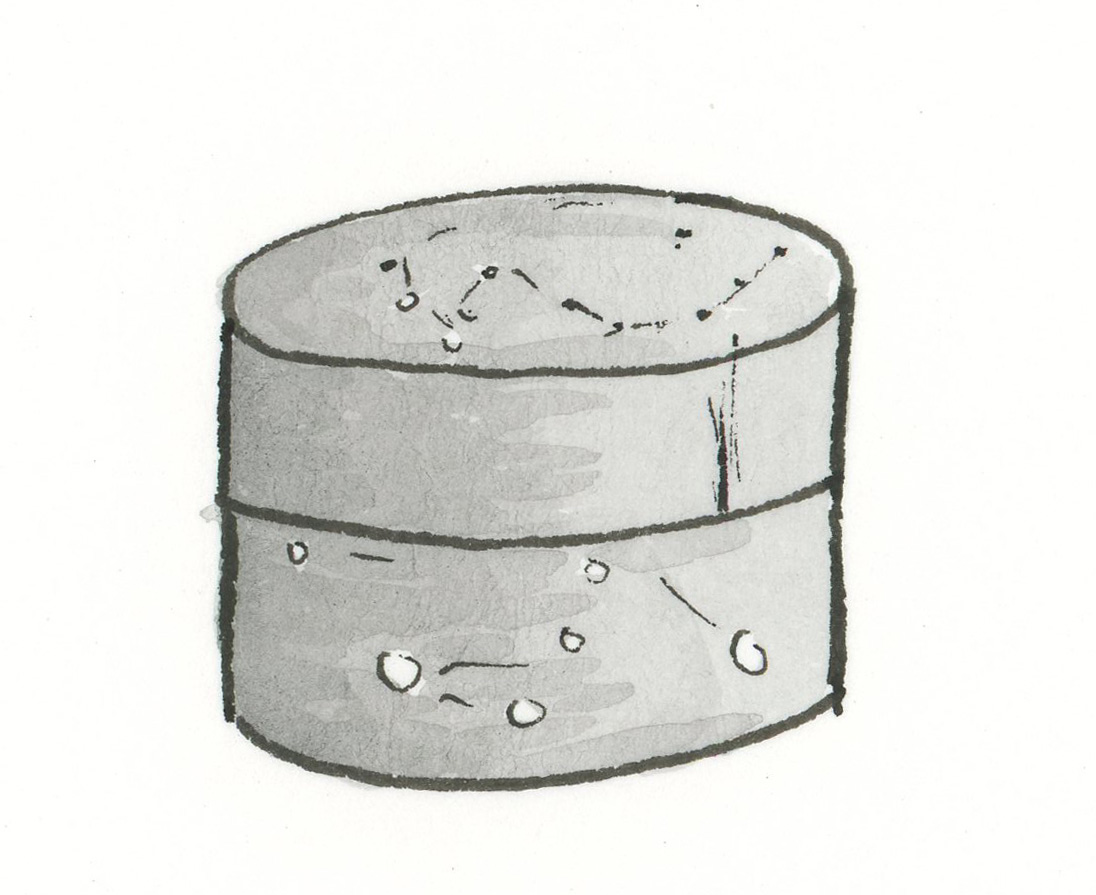

I had told my professors about my dad’s condition, in case of an emergency in which I needed to leave immediately. They were extremely understanding and sympathetic. The topic of my dad’s situation played a part in my studio work. In my metals-mithing class I made an incredibly tiny cylinder container with a lid. The metal had been pressed with leaves from the magnolia tree in our front yard that my dad had mailed to me earlier in September. Delicate veins of the magnolia leaves run on the surface of the copper container.

The project was dedicated to my dad and my family. The top lid had carefully hammered silver rivets that formed the constellation of my dad’s zodiac sign, all connected with delicate lines cut by a tiny saw. The sides had my mom and sister’s zodiac constellations as well. It was an ode to my family, bonding with my dad, his love of space, and our telescope nights in our driveway. I must have done thirty rivets on a tiny container no bigger than an inch in diameter. To say it was difficult to do would be a massive understatement. But it was made with love, patience and determination.

Living in Oklahoma I was always home-sick. There were things I constantly missed about Houston, mainly food-related. Besides art, food has been my second love. I even considered being a chef for a while before I found out how physically demanding it was. My whole family loves cooking, I inherited that from them. My parents are great cooks and I watched everything they did. I was a sous chef from the age of six, peeling garlic and grinding it up with peppers in the molcajete.

My mom and dad had two different styles of cooking both cataloged in my mind now. She was precise, tiny chopping, while he was blunt with liberal proportions. Images of green onions, garlic cloves, avocados and cilantro take me home to our kitchen. We didn’t follow recipes on paper, our cooking was more like stories you memorized. When I found out Jon was a vegetarian, I took that as a challenge to translate all the delicious recipes I loved for him. Food was a big part of our life.

Since I had left Texas I mostly complained about the lack of grocery stores that compared in size and selection. My parents told me about how huge our newly remodeled grocery store had become, I was deeply jealous. I love food so much that I had recurring dreams about this expanded store, going up and down the aisles, getting pastries or exotic fruit. I always woke up before I could enjoy anything. In general, I had been missing home for years and daydreamed of finally seeing it in person again. Now the circumstances of returning were for different reasons.

•

The semester was coming to an end. One of my last classes went out to lunch together. As everyone was leaving, I told my professor about my dad. She knew he had been sick and I hinted that Christmas break would be our last together as a family. I hadn’t gotten much further when she suddenly burst into tears. I was standing there, in a sandwich place, nervously watching this woman break down crying about my dad dying. I hadn’t prepared for this!

I was so proud about how emotionless I had been, keeping a professional face. Now, I had just made someone cry. She told me about how much she thought about her mom, who had passed away years earlier. She showed me the needlepoint on her Christmas vest she was wearing that was done by her. I felt bad for being so reserved while she was freely moving through her feelings.

Meanwhile, a few days later I had another professor who refused to show any emotion when I talked about my dad. During a more emotionally difficult day and moment, I let my guard down and revealed how painful it was that my dad wouldn’t see me graduate. She smiled uncomfortably and nodded. Sheepishly, I regretted being so honest.