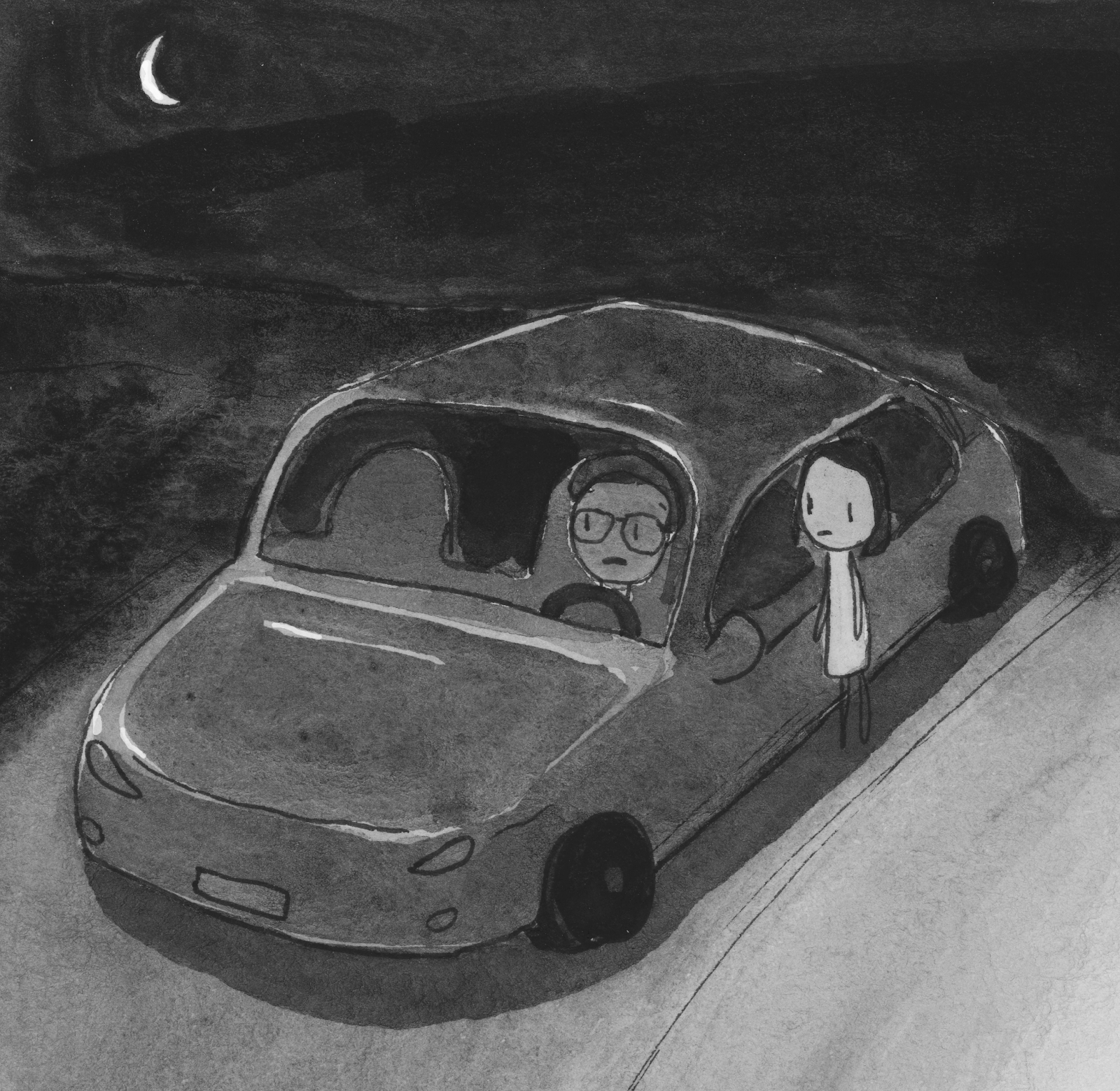

I wanted to spend my entire break at home but Jon could not get out of school at the same time as me. So instead I flew down to Houston the first moment I could. My sister’s friend offered to pick me up from Hobby airport. I remember the car ride back to my house, the traffic, my sister’s friend Shannon being kind, the chit-chat about how much the city had changed. I remember how normal the conversation felt in the most un-normal circumstance.

I hadn’t been home in three years. We talked as my eyes absorbed the familiar places, streets, fields, stores, and intersections. The usual joy of going back home was now an agonizing confrontation. It felt like I was in a space capsule, hurtling faster each second back down through the atmosphere. All the while I pretended not to notice the terror and anxiety. I was about to hit an ocean of pain.

It was a warm evening and the sun had begun to set. There was a pale blue light, with pink and yellow flames brushing across the sky. My mom came out into the driveway and I got out to hug her. I could tell she hadn’t showered in days. She chatted with Shannon and began to choke up. My mom motioned that my dad was inside. It appeared that she did not want to be with me when I went in. She nodded her head and held back tears. I knew this was bad, this was definitely a sign of what was waiting. I walked toward the garage door that led into the kitchen. The door I’d seen a million times before coming home, right next to the washer and dryer. I pushed it open knowing it was now an entrance to a different place.

Closing the door behind me, going into the kitchen, it was quiet. Without hesitation, from the airport to the door, I kept going. My legs kept going even though my blood was now ice. I knew things were bad but I had no idea what to expect. I turned the corner and there I saw my dad for the first time in months. He was sitting in his chair, as always. But now he didn’t move. Internally I could feel myself screaming.

My dad was gone, someone else was sitting there. My eyes took in the skeletal form sitting in front of me, grasping to make sense, stumbling through what felt like an eternal shock. It may as well have been an invisible grenade that I had walked into. I wasn’t prepared. The burly man I knew as my dad was now bones, literal bones. Images that I had only ever seen in pictures of the Holocaust. Pictures of suffering and cruelty. This was my dad now. He couldn’t even move. His arms were placed carefully in front of him on a pillow as if done for him.

For only a second my mind crashed but I absolutely refused to miss a beat, knowing he was miserable at the moment as well. I mustered an awkward attempt to maintain normality for his sake. I knew he was ashamed to have me see him in this way. In the agony of that moment, the only thing I could think to say was, “Hey, how are you feeling?” I sat down on the couch nearby him and attempted to look calm and make small talk which I can’t recall. I felt numb.

After a while my dad seemed to relax a little, his sleepy, broken spirit had shifted into a more upbeat tone. Maybe because the pressure of the moment had finally passed. Now his nightmare of having me see him had ended. My mom eventually came back in. We talked about the plane trip and then what to do for food. He wanted to get a pizza but I had to remind him that I couldn’t eat bread anymore and he chimed it probably wouldn’t be good for him either. I volunteered a trip to the store to get things they need. With an itemized list in my pocket, I took my dad’s keys and made my way out of the house.

•

Escaped, I still had no emotion. I sat in his car, in our driveway, the darkness encroaching. The interior was worn down, unusual for my dad who always took the greatest care of his cars. Most shockingly and out of character, he’d begun smoking inside it. Ashes filled a tray, overflowed, and then sprinkled out beyond. Signs of my dad’s decline all around me, his inability to find the energy, hope, or care to maintain as I’d known him his whole life to be. The radio didn’t work and I barely knew what to do since I’d never driven it, or any suv. In the dark, I headed to the store.

After parking, I realized I didn’t know how to turn the lights off. I fumbled for about ten minutes, turned the car off and then on again. Then cursed for a full minute gripping the steering wheel, wondering if anyone could see me. In a panic, I considered asking someone for help, but that’s when the lights suddenly shut off on their own. Life is a comedy. I had not yet experienced the advancement of automatic lights.

Getting past that embarrassment, I went in and anxiously got all the stuff we needed and headed to check out. All I could think about were the dreams I had about this “incredible” store I’d built up in my head and here it was, a regular store. Standing in line, my mind buzzed while I drifted in and outside my body. Sounds echoed around me. I was home again, but my dad was dying. I just drove the ruins of his car to the grocery store.

Trying to digest everything I had just seen, I was too numb to cry, too nervous to react. For years I had literally dreamt of returning to Houston and shopping in this store. Now it had happened, in circumstances I had never seen coming. I felt like an idiot. At that moment it began to hit. All around me other people, parents with their kids, laughed, smiled, carrying on with their normal lives. To them, I looked like a normal person. I was standing there but no one could see a person whose whole life was burning down.

A few days after my arrival, my dad began to pep up a little. My mom happily noticed a difference in my dad. The new comfort and security of me there to help them improved his mood a bit. My dad was still trying to appear autonomous. To my uneasiness, he drove us to the treatment appointments, insisting he was fine. I still remember watching him swaying like a branch in the wind while getting gas. He was still trying to be the man, the dad performance he’d done all his life for me. I was terrified at him being behind the wheel but he refused to let me drive. This was a man who didn’t know how to not be in control. He looked terrible, wobbly, but insistent and stubborn as always. I didn’t want to fight with him.

I wasn’t prepared for the experience of chemo trips and followed my mom’s cues. She had a whole bag of stuff ready. It took almost two hours for the whole thing to be done. We’d go in and wait for his name to be called, meet with the doctor, then go to the area set up with recliners to get the chemo. My dad reclined in a chair while they hooked tubes up to a port under his skin.

Like a scared cat, I glanced around the place, taking in what they were already used to. I felt a lot of things and hunger was not one of them. But as soon as it was over, he sprang up, cleared his eyes, and announced, “Where do you want to eat?” I felt like either dying or throwing up.

•

We went to a restaurant my family had frequented before I had even been born. It was a Chinese and Vietnamese place on Nasa Rd. 1. Some of my fondest memories had been at King Food and it was usually my birthday request. Over the decades my parents had become friendly with the people who owned it. It had changed so much as the years went by and I hadn’t been there in ages. The restaurant was five minutes down the road from the treatment center and ten minutes down the street from our home. We sat down in a remodeled booth. It didn’t feel the same, it all looked different. I sat shrunken, juggling a life’s worth of memories of this restaurant. I had a new bleak memory sinking in, my first trip to the clinic. How on earth I was going to eat?

It was late afternoon and there were only a few people inside. My dad was energized, as much as he could be anyway. We ordered and I was surprised at how much he was eating. It was important for him to eat as much as possible, especially right after treatments because as the days progressed, he would feel much worse and would curb his appetite. Eating became a chore. Pancreatic cancer stops the ability to digest normally. This issue coupled with all the medications my dad was taking meant that every time he ate, he was under an extreme amount of gastrointestinal stress.

Soon he would begin belching loudly, often in series. It was alarming and somewhat embarrassing. He was a bit cheerful that we were together, that he had eaten so much food, it was a small victory. But now he was belching. I couldn’t help but see the eyes and glances from everyone in the restaurant. Looks of judgment, bafflement, annoyance, of disgust. They seem to look at my dad and surmise he was a rude, grotesque elderly man who didn’t give a shit.

This would become a common judgment in public situations that upset me endlessly. Others, outsiders, would look at my dad and see an elderly man of eighty, maybe older by his diminished state. I sometimes wanted to scream, to yell at them; he was my sixty-five year old dad and he was dying of cancer! He couldn’t help it, he couldn’t control a single solitary thing. My dad showed no sign of noticing the others or maybe he didn’t care. His mind seemed often busy elsewhere.

•

It physically hurt to look at my dad. I couldn’t help it and it made me feel terrible for thinking it. At home sitting in his recliner, his legs were no longer muscular and lean, only bones remained. He had trouble sitting, sleeping, everything. We ordered a medical type of mattress pad made with thick foam in hopes he could get some relief at night. It made a mild difference. You never realize that all your muscles and fat are what keep you buffered on every single surface. You take for granted your body naturally keeping you from hurting twenty-four hours a day.

His skin on his face was dry, with patches of weird blemishes I couldn’t understand other than maybe due to lack of vitamins and proper organ function. He no longer had any of his iconic Astros hats. When I asked about the UCO hat I got him, he said nothing fit his head anymore, because it had shrunk. He now instead had two navy blue caps, they were noticeably smaller than his usual size. In fact, all of his hats were gone. He had thrown them all away for some reason. Even his voice was different now, softer, and for some reason, it sounded nasally like he had a terrible cold. This is the way things were now and I never got used to it.

My mom and dad were stressed out by bills and paperwork. Mail came in bulk each week. His company had sent a fancy Christmas card and all the employees signed it. I remember one person had written as a joke, “Don’t die!” my sister murmured, “You know that guy’s going to feel bad about that.”

During this two-week holiday stretch, my dad watched tv all day, sitting uncomfortably in his chair. At one point a Wolverine movie was on and Jon and I sat on the couch watching too. There was something morbidly sad about my dad, in his state, watching a superhuman form played by Hugh Jackman on screen, muscles flexing, saving the day, and killing the bad guys. I didn’t know what my dad was thinking but he kept watching silently, never changing the channel.

Sometimes he looked angry, but mostly I think he was hurting. This wasn’t exactly inviting, I mostly sat on the couch watching whatever he was. The tv was always blaring and usually on some sort of terrible show about people selling things. He seemed determined to avoid any television that had a story. This was something I found out the hard way by attempting to put on comedies in hopes of lifting his spirit. He still sat aggravated, as if knowing what I was doing. I quickly gave up. He’d sit there, shifting in the recliner until eventually, he had to take a pain pill. My dad was afraid to take too many pain pills. He was afraid of building up tolerance and then needing more. He was also old-fashioned and didn’t want to take the pain pills. He was stubborn, absurdly so.

We tried in the most skillful of measures, not to think or talk about the fact that this was our last Christmas together. We were all mentally exhausted. While on a shopping trip with my mom and sister for some crap among the masses, I saw an old acquaintance and immediately walked away. Someone we all knew. There was no way that I or any of us could have a conversation with someone who knew our family as it had once been. We had no energy to stop and explain the grim horrors we were dealing with. We just couldn’t do it.

A friend of my mom’s that she’d known since I was a baby came by to visit one night. Earline and my mom had worked together decades before I could even recall. She was a bit older than my mom. She’d known our family for decades and would sometimes eat dinner with us. She had pulled up to the driveway one dark evening, not wanting to take up too much time. I hadn’t seen her in years. As my mom got her gift together inside the house, I chatted with her in the driveway. I still remember her face, sad, shining in the dark.

Her eyes fixated straight ahead at the house, knowing the circumstances beyond the doors. Sorrowfully she said, “I am so sorry about your dad. He is a good man.” I nodded back. I’d known this woman most of my life, as a child, in the back of her car while she was helping my mom run errands. Neither of us would foresee a time in which on this night, under these circumstances, she’d be offering condolence of such a horrible situation. I guess no one ever does. I appreciated her words, I’ll always remember that moment and what a great friend to our family she was.

The most painful part of our last holiday season together was certainly New Years. Counting down to midnight, watching people celebrating while my dad sat grimacing in pain, was the ultimate cruel joke. My sister and her husband had to feign customary excitement for the sake of their kids. Everyone was trying to be normal, or some version of it. I remember sitting there that night, wanting to scream in hysterics, but nothing came out. I sat there on autopilot. The giant 2015 sign flashed in excited lights on tv and my dad stared uncomfortably at the year he would not live to see more than two months of.