Some older nurses came to the house and frantically started to hover over my dad, which I knew he hated. “They act like I’m going to die today,” he said in an aggravated huff. A bed was delivered and a man set it up in the living room. My mom chatted with this man who described how his son had died from a terrible disease. That experience had compelled him to do the job he now had, helping others in those dire, familiar situations.

After the information dump from nurses and brief chaos, the house resumed to the usual quiet. Now that he had nothing to fight for, my dad seemed hopeless. We were all drained. I quickly tried to eat a sandwich, away from him in the kitchen. As usual, he was mad about the whole day and was barking orders. In the most logical way, I knew he was miserable, but physically I was worn out.

He was snapping directions when I came around, out of the kitchen, my frustration likely showing on my face. Shameful and apologetically he quickly said, “Oh, are you eating? I’m sorry, I’m sorry, go eat.” and in an instant, I felt like shit. I couldn’t manage to keep it together for one moment? For his sake? But there was nothing easy about any of it, each moment, each minute. Nobody told me or warned us, how it would be, how stressed and stretched thin we would all become.

In these final days of my dad, he was not sitting and having sweet, introspective moments with us. That relentless pain makes you angry and miserable. All of our last minutes, days, and hours with him were sad. We knew it was the end and yet he still maintained a lack of emotions. He was resolved on the fact that no one should be called or warned about the situation. In one instance he demanded, “I don’t want a bunch of people crying.”

On tv there was a popular show that featured a story line about a mom getting cancer. Of course, she makes it. Her token Latina friend doesn’t make it. During this time in my life, the story line was about the dad dying, but he lives to see his daughter get married! …and then dies… much later, peacefully in his chair at home, asleep! So everyone gets their saccharine dipped resolution. No painful stuff because that would be awful. It made me so incredibly angry.

I get it. Logically no one wants to watch sad stuff. No one wants to see terrible things happen because life is ALL about trying to avoid awful, sad things. But still, it felt like a slap in the face to be reminded in so many ways, we were living the story SO SAD, no one dared to show it. I was living the worst plot, the one people turn off and can’t be bothered with. I was aware that it was unfavorable content for a tv show, but what the hell was I supposed to do? I couldn’t turn it off, it was happening. My jealousy and resentment of the living was out of control. Life and the world were for healthy people and we didn’t belong there anymore.

•

A wheelchair that had been delivered to the house, sat in the living room and my dad tried to focus on it. “Put that right over there, so I can see it,” he said weakly with determination. My dad spent the night in the hospice bed that evening. I noticed he was straining to see the tv and didn’t seem to care much if he was missing his favorite show anymore. The metal railings of the bed were dark maroon. A foam sticker of a fuzzy, yellow Easter duck was still intact. Easter was still a few weeks away. I imagined a small child had put it there, where their grandparent had died, days earlier. I knew it was over. I’d seen it with Jon’s grandfather. Typically, hospice meant you had days.

My dad hadn’t eaten all day or the one before that. The doctors had prescribed him morphine. A nurse showed me how to crush the pills, mix them with water and use a plastic pipette to siphon it up, then plunge the mixture into the corner of his mouth when he could no longer drink. This hadn’t been necessary, but the new information made a wave of icy fear pass over me as I stood trying to appear competent.

•

Alone that night, things seemed grim, noticeably different. We didn’t talk about the fact that he hadn’t eaten all day. We didn’t acknowledge what it meant in his frailty that he had barely eaten the day before or the one before that. It was the saddest night, knowing it was all a lost cause. Alone in my room, I wrote:

“There is a numbness that buzzes through my body. It hurt initially because it was my dad, my mom, my room, my home. But now nothing is what it once was. It’s all unfamiliar, it’s become something else. It’s all disconnected. He is going to die. All this will end. I will only have a mother. I will turn thirty-three. I will graduate and I will never live in Houston again. Everything I remember is gone.”

•

Saturday was another eternity. My mom placed a photo of me and my sister next to him, he tried to look at them, blinking, straining. I didn’t have the courage to ask if he was still able to see.

My dad didn’t want me to see him struggling as he now was. He whispered to my mom not to bother me as she helped change him. My arm was also an issue. I was still wearing an elbow brace, along with hand and wrist guards because of all the amounts of grocery lifting I was doing. It always killed me that even then my dad was still worried about me. He had told my mom alone, “make sure she goes to the doctor for her arm.” My mom was dealing with her own issues. Her hip and back pain were getting aggravated by all the physical support she was administering to change and bathe him.

That Saturday afternoon, due to the lack of eating and new drugs in his system, my dad started to feel sick. I was sitting in the kitchen, listening to my mom help him out of the bed over to the plastic toilet a foot away. A moment later, smells began to fill the room. In his weakened state, the smells started to make him ill. He began gagging and retching, trying to vomit. I sat still, marked with both terror and pain as the situation unfolded right around the corner. I still remember my face, incredulous maybe even a little disgusted at the insanity of it all, the total cruelty of the situation. It seemed unfathomable, he was starving and now he was vomiting.

Upon hearing my mom struggle I ran around the corner to help. He was slumped down, chin over his knees, my mom trying desperately to lift him over to the bed. I sprinted over full of adrenaline, expecting to lift him. What I didn’t expect was that my dad, who was literal skin and bones, to be shockingly, quite heavy. I wrapped my arms around his hips behind him. My feet flat, squatting and my knees locked with all of my efforts, I tried in vain to pull up using my legs. This was my usual reliable source of great strength. My mom struggled, pulling up under his armpits above me. It felt like there was some off-screen villain had a beam on us, draining us of all our power. My mom and I could manage nothing more than keep him upright. It felt as if we were lifting steel.

Terror ran through my blood. I didn’t know how we were going to move him onto the bed. In this sad moment, my dad softly urged, “Don’t hurt your arm, Shell.” Then somehow, through a small amount of energy summoned, he collapsed back onto the bed that was a few inches away. He laid there, cold sweat, his skin a gray-white. I was in a daze, rattled, terrified at the new frontier our life had crossed into. It was the last week of his life, the most stressful of mine.

•

Sunday morning I heard my mom bathing him from the back of the house. As I laid in bed I could hear him moaning in what seemed like terrible pain, but was apparently relieved. He was soothed, telling her it felt like a massage. His aching body could no longer relieve the intense itching of dead skin that had built over the months he was sick. He told my mom afterward to go lay down and rest.

As he slept I went into the kitchen. My emotional house of cards was no longer able to sustain itself. There was nothing left to say. I broke down crying in front of my mom. The only time. Shocked, she tried to comfort me, “What’s wrong? He’s going to be okay Shell! He had a sponge bath, he felt good, he’s resting.”

My head hanging inches over the counter, shoulders jolting with each sob, she rubbed my back. I wanted to say to her, “no, he’s going to die soon,” but I couldn’t.

•

He was starting to sleep most of the day. Due to his stomach being filled only with medications, his breathing was releasing a terrible smell into the house. Something we pretended not to notice. It had always been like that while he was sick, but for some reason now it was worse. Medications and stomach acids filled the room.

I tried to make sure to stay with him that weekend. Even though he was asleep, I didn’t want him to be alone. I couldn’t stand the idea of him being alone. He was starting to leave us. Slowly he was awake less and less. My sister and her family came by for a day. The kids talked to him, I watched from a corner. A guardian angel candle flickered nearby.

The next day I sat across from him, reading my Frida Kahlo book, the person who lived through many hells. I thought if Frida could endure the worst, I could also manage somehow. Every so often my dad would wake and look around. Blinking in the dim light, scanning the darkroom, he’d find me, relax and smile. Eventually, he would close his eyes and nod off again. My sister and her family left that afternoon after saying what they thought would be their last goodbye.

•

The afternoon sun leaked through the windows. In the living room, the lights were off. My dad slept in his bed. The weather had transformed into a nice warm day. Winter was gone and it was fluorescent, spring outside. The windows were open, airing out the sickness and a soft breeze flowed inside. Bright green anoles perched on walls and plants. Through the window screens, birds chirped. Everything was quiet and peaceful.

As I sat in the kitchen finishing lunch with my mom. I swore I heard a woman quietly crying, coming from the other room. My mom washed dishes and did not seem to notice the sounds. I ignored the irrational idea of what I’d heard. Then a while later while I was still sitting, I swore I heard a woman’s voice announce, “Hi Mike.” It sounded so real that I walked over to the living room, eyes wide, nervous at what I might find. Slowly peering into the dark cool corner, my dad still slept.

I walked to the window and scanned our backyard. I waited to hear neighbors that would explain the voice but heard nothing. The enormous philodendron that grew for decades, sat in the courtyard. Its deep green and ruffled leaves swayed slowly. An anole perched still.

Nobody was there, nothing I could see. I thought of my grandmother. I thought of my aunt, whom I’d never met, my dad’s younger sister Alicia. She died tragically in a fire when I was a baby. Were they here, somehow? Why had I thought of them? In my dad’s sleep, was he going somewhere else? Or was somewhere else coming here to him? I didn’t know.

•

As a kid, one of the most mind-bending ideas I’d ever heard of was the theory about other dimensions. My dad explained to me our five senses, about how we understand our reality based on them. At the age of eight, this was startling. It was exhilarating to imagine that the limitations of our human five senses could mean a possibility of things existing beyond our means of comprehension. For a while, I had an imagination that perhaps there was a portal somewhere in our house to another dimension! I assumed, unfortunately, I would never find it because of my poor limited brain. But I still spent time looking, driving my toy cars into random parts of walls hoping for a secret entry to take shape.

I’m not religious, though I had tried to be in my youth. My only experiences with death was at young ages and involved murder, infection, and suicide. Experiencing those horrible and unnatural deaths of people ages 13-23 kind of shut down any ideas that there was a “plan” for anyone. I tried for many years to believe and eventually couldn’t do it anymore. Still, I don’t necessarily believe there is nothing.

I definitely feel deeply that something is out there beyond what we see, something I’ll never possibly know. When I look at my cat, she has no idea that there are streets outside, what they mean, where they go, what a map is, what the internet is, or how the vacuum works. She doesn’t know there are countries, oceans and galaxies. What if there are things beyond my senses, beyond my sense of colors and sounds? How would I even know? It definitely feels sometimes like it’s not supposed to be known, whatever it is.

As my dad drifted away, I considered where his soul would escape to, what he would become. Would he stay with us, would he remember us? Whatever the essence that is “us” might be, when it leaves. It’s the only thing I can’t help but believe, as irrational as some might think. In this dire time, I stared at my dad wondering where he was going. I wasn’t ready to let him go but I was in agony over his quality of life, for what seemed to be just torture. The thought of him leaving was destroying me. It was hard to admit, I wasn’t as tough as I thought or wanted to be. The reality had set in, I was going to have to say goodbye.

•

By Monday, things had changed again. My mom and I were by him, the lights were on, it was early afternoon. The effects of not eating for three days were starting to finally show. He was making less sense, his thoughts were getting clouded. At one point he asked what time it was and I said, “It’s 3 pm, Monday.” He then paused and said, “Howdy doody time?” My mom and I laughed and exchanged nervous glances and he said, “No, I’m serious! That’s the time it would come on when I was a kid.” A minute later he looked around and asked again, “What time is it?” I said it was the afternoon, Monday 3pm. His eyes, wild and round, struggled to take in his surroundings.

I could see him trying, his brain fighting, looking for the words, the thoughts. This time he said, “Is it Tom Brokaw time? Is it Nightly News time?” My heart was crushed. Both my mom and I didn’t say much. His brain was operating but on only a few seconds’ worth of memory, it seemed, before getting lost again. He was now making a face that seemed worried, maybe even scared. Did he know something was wrong, inside his own mind? Did he know it wasn’t coming out right anymore? I could only guess.

A while later we helped him sit up, get his pillows comfortable. My mom and I were on either side of him when he drifted off to sleep. We stood there watching over him for a while. Then my mom started thinking about our own physical state. She said, “Maybe you should go out and get us something to eat.” As she suggested something, my dad with his eyes closed, started talking, “That’s probably for the best” and smiled. He drifted out again and we stood silently.

A few minutes later after we thought he’d fallen asleep, my mom was naming some places to get food when he suddenly said with closed eyes, “Yea, I’ll have myself a little…” and tried to motion with his hands, weakly as if holding a burger, but then drifted off again. His brain still wanted to believe it could keep going, like the weeks and all the days before. I understood how much his brain wanted it to be like it was, we all did. It killed me inside.

Later that night suddenly, my dad awoke. My mom and I suggested water but he grimaced in absurd disgust at the idea for reasons I’ll never know. Then quite strangely he requested a beer. How could we fight? He talked a little, took a few sips. His eyes were still wild, round, maybe because he couldn’t see much. He kept asking about Jon, “Does he know how to get here?” Things were not the same, his questions weren’t making sense. It was the last thing he ate or drank, not counting medication. This was the last real conversation with him.

•

The next few days are a blur. I mentally broke apart and was barely eating. Realizing he was not waking up much anymore, I retired to the backroom to intermittently sob and watch tv. I made desperate and lonely drives to the dollar store, that used to be the grocery store where we’d always shopped. Where he had defended my honor against the rude woman.

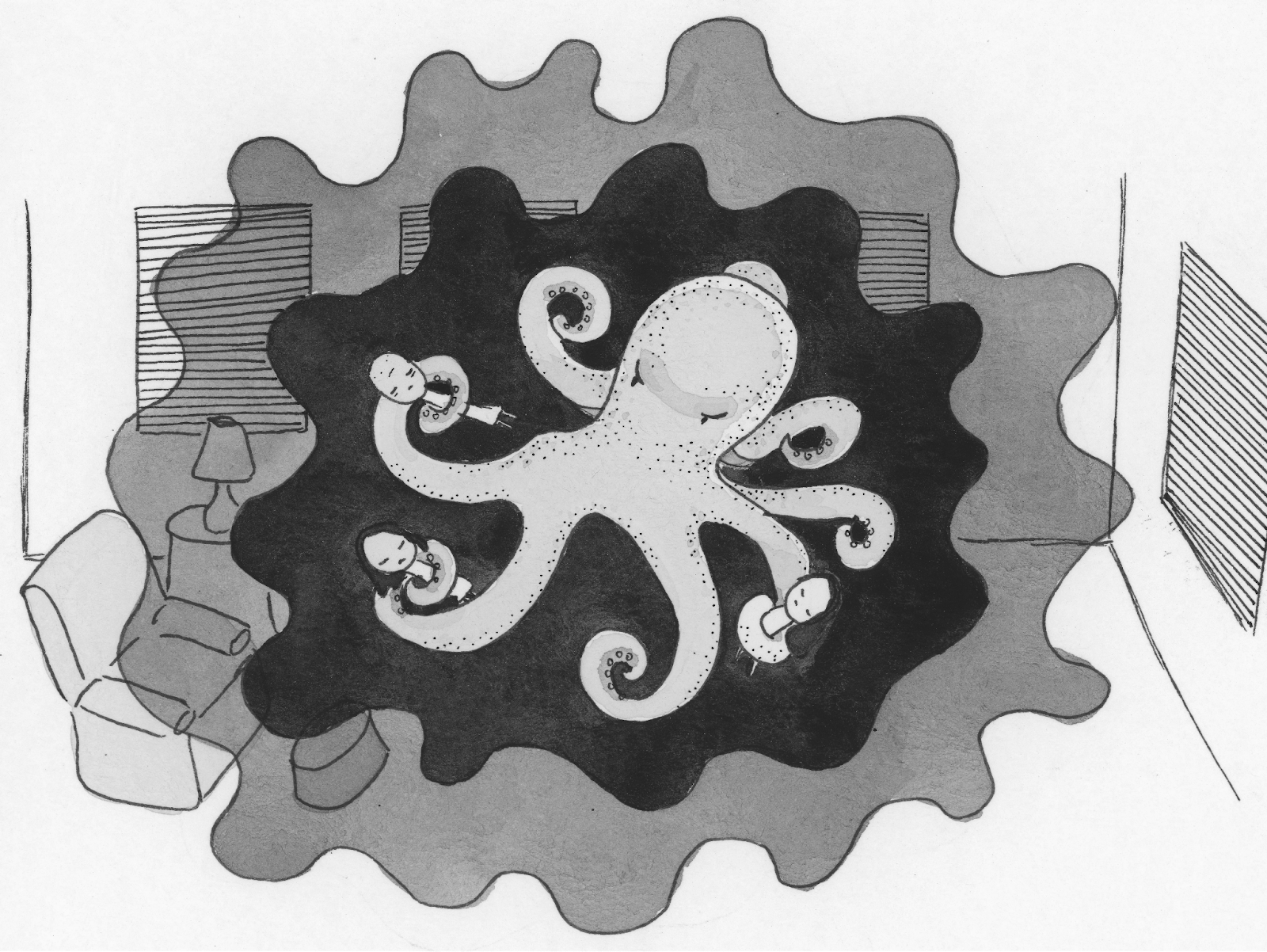

Now I was standing in line at the register, holding four guardian angel candles. I knew how stupid it was, burning these candles as if he were lost and they would help him find us. The woman in the checkout wouldn’t know what kind of hell was washing over my life. It may as well have been a black, poisonous ink of a mammoth evil octopus, engulfing every square inch of our home.

My home and life were in ruins. I was in a daze as I stood by helplessly, watching my dad drift away. All the while, the whole world went on with its normal routine.