In my mind, there was a laundry list of things that could have caused my dad to have cancer. Starting from whatever pesticides that were in the migrant fields around him as a kid, working on oil rigs before he was sixteen and exposure to who knows what during Vietnam. Then working in a chemical plant for decades and of course, all the shift work that went with it. There were a lot of possibilities.

I continued thinking of what else could have caused it. Sometimes I was angry at him. Maybe if he stopped drinking and smoking he’d still be alive. He had always laughed at the idea of getting cancer saying, “Everybody in our family’s hearts gives out before the cancer ever gets to us!” In the past, this would have been true, had it not been for all the cholesterol and blood pressure medications readily available to his generation.

He believed the old food pyramid advertising eating meat multiple times a day to be healthy. He’d been a poor kid, who finally had an abundance of food as an adult. Food always represents wealth, success, celebrations, traditions, and happiness. It was now the opposite of his memories in which food had to be limited, using bits of meat to season meals in order to stretch money further.

Like most people, no one in his family understood or practiced proper nutrition let alone portion control. My dad failed to see the connections between excessive eating leading to diabetes, which then begins ushering in the possibility of various cancers. By 40 he was slowly filling the checklist for pancreatic cancer and didn’t even know it.

•

Shift work and lack of a reliable sleep schedule completely affected our entire family. My mom would often stay up late to be with my dad, which also meant me and my sister would join them. Out of what I assume was guilt and sadness, my parents didn’t police us because it was our only time together.

Our family never had a normal schedule, no one went to bed at nine or ten pm every night. We were all night owls, something I didn’t recognize as a serious issue until my twenties upon seeing how other families lived. As far as we were concerned, we were having fun. It wasn’t unusual to find us up at midnight, eating, laughing and watching movies or MTV with things like Bruce Springsteen’s video Dancing In the Dark playing. A highly specific memory I can still recall.

We didn’t know about all the studies that would show how essential quality sleep is, or that going to bed at the same time each day is also equally important in repairing cells within one’s body. Until I die, I’ll probably always struggle with staying up much too late because that’s what I equate to happiness. It was just normal for me, for us.

Almost immediately after my dad passed away, my ten-year lack of dental insurance became a perfect storm of multiple failing cavities. One molar, in particular, was giving me trouble trying to sleep at night. I began to panic that it would become a full-blown toothache and did not want to experience the horror of just how bad it could quickly get. In haste, my mom made me a dentist appointment to get it taken care of.

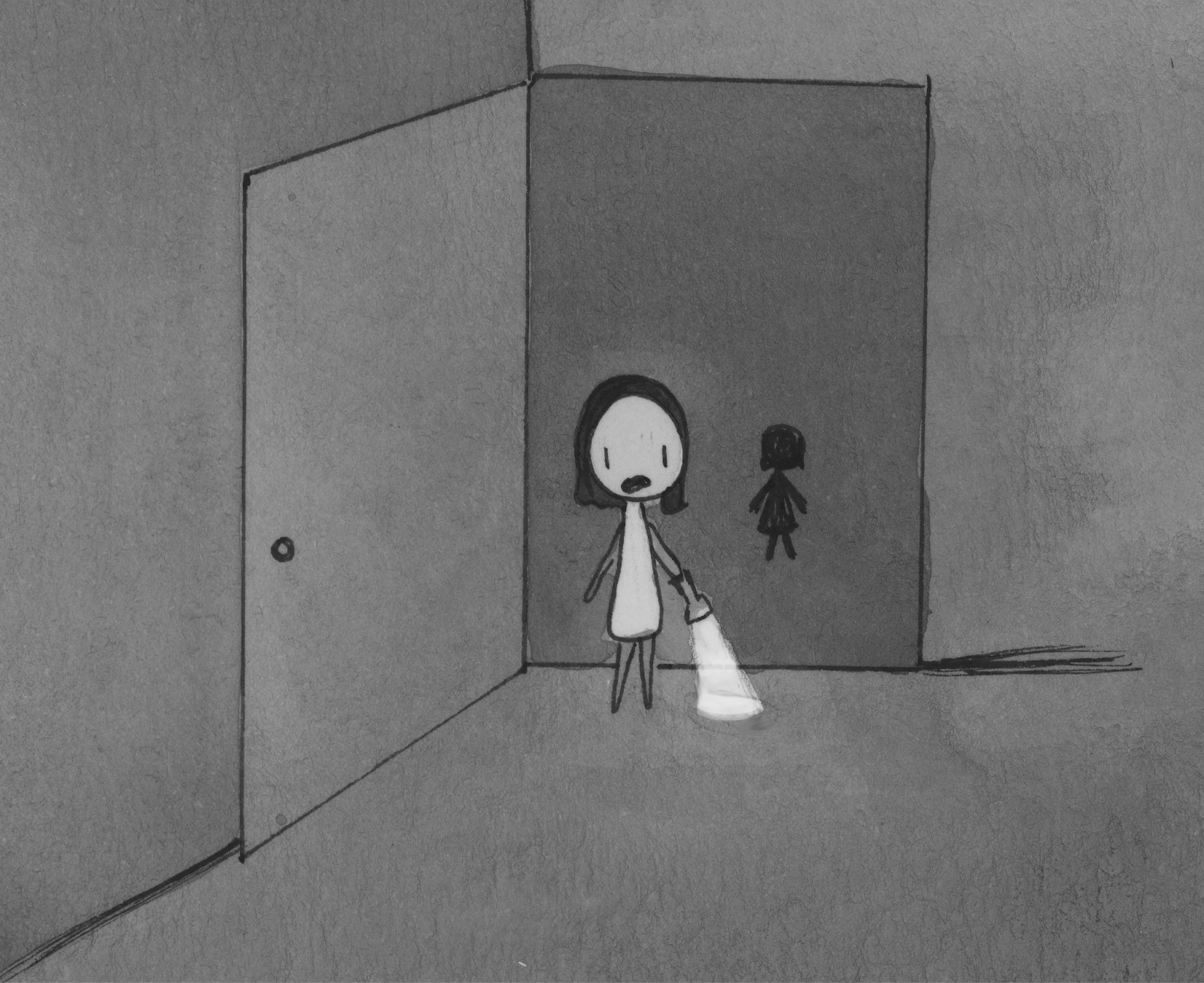

I forgot that my parents had switched back to the same dentist I’d seen as a child. In an ultimate horror, I found myself in my dad’s car, sitting in the parking lot waiting to see our old dentist. Thoughts flashed of all the times my dad had driven me to the dentist as a kid, the trips in the van, my tiny legs dangling over the seat. All those days I took for granted, all those moments when I had someone taking care of me, in ways I couldn’t comprehend. Now I was unarmored, lost and terrified in this world. I felt childish thinking about how lonely I felt, even though I was an adult. Then I felt more embarrassed for not being stronger. Inside the dentist’s office, the anxiety came on quickly.

I was up too early, sitting in the waiting room alone. I had not seen this dentist since I was a child. I became very aware of everything. All the memories, the bad modern art, how old I was, jobless, my dad’s death, my whole life fractured and then… the panic really set in. Silently, my breath and pulse quickened. I was a failure… I’m in Houston? I’m alone? I listen to metal? WHO AM I? WHAT AM I DOING? HOW DID I GET HERE? With each second passing, it felt like I was expanding. A new terror emerged that I was now genuinely unfamiliar to myself. Confronted with who or what I thought I was for my entire life, sent my mind into a disorienting existential crash.

Then suddenly, the doors opened and a lady called my name. So of course I acted normal.

I nervously sat reclined in a puffy chair, embarrassed as my teeth were cleaned. Eventually, my old dentist came in, exchanging usual pleasantries. With his mask on, he asked how my dad was doing. “He passed away in March from cancer,” I said awkwardly with my little bib on and light in my face. His eyes froze in disbelief. After the usual condolences, he and his technician went back to work.

Toward the end, while they counted my cavities I thought I heard a few laughs at my expense. I’d have to come back to get four fillings. When I left, the woman behind the desk didn’t seem happy about the fact that my mom had asked to pay in installments because of the large bill. The receptionist couldn’t be bothered by my mom’s traumas or the long story of my dad’s illness, as she overheard my mom talk to the dentist. It seemed like our momentary poorness and sad story were just a nuisance to her afternoon. I now understood why emotionally or fiscally struggling people don’t bother going to a dentist at all.

•

One of the days my sister and niece were in Houston with us, there was a torrential rainstorm. Against the windows it looked like a washing machine outside, churning wind and rain for over an hour. The power went out. My dad’s emergency storm radio, tv, and mega light contraption came to use that evening. We sat in the dark listening to music, eating garlic pistachios and spicy corn nuts. My tiny niece sat on my lap, while we were all together in the overly humid living room. We sang along to the Beatles, Hello Goodbye playing on the radio.

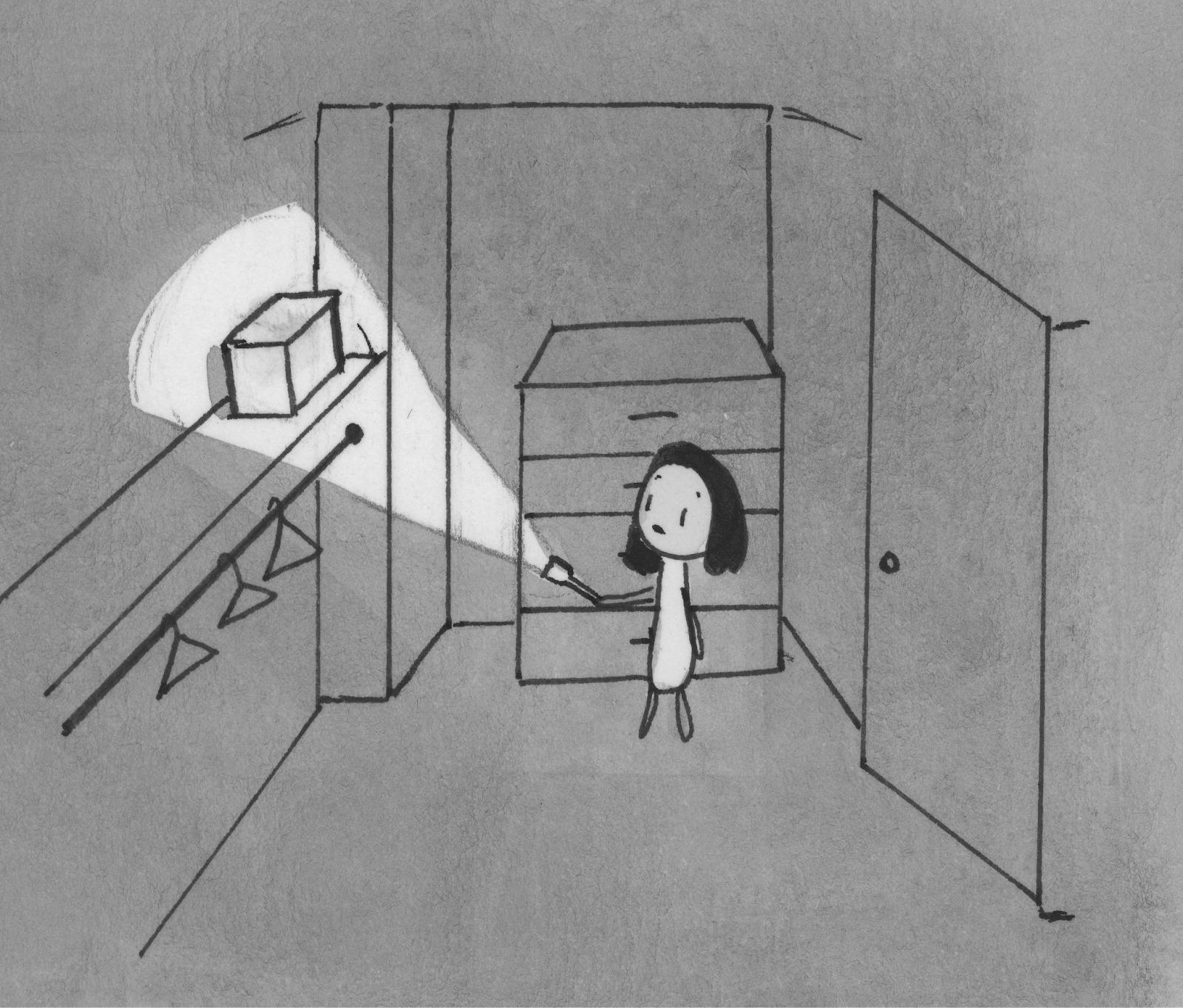

Looking for another flashlight, my mom sent me into their room. I went into my dad’s closet looking to retrieve a box with an l.e.d. flashlight from his company. As I searched in the darkness, the beam of my flashlight landed onto his box of ashes, sitting atop a shelf. Not expecting it, I jumped in fear.

A jolt of pain ran through me. At first, I was annoyed at my mom, why would she do that? Why would she leave his ashes up here, of all places? But then a few seconds later I realized, my mom wasn’t ready. I was starting to see that everyone’s monster was different. There was an invisible entity tormenting us. We were all affected by this shape-shifting monster. We were bumper cars in a dark room, each running from something different, hitting each other inadvertently in the process. She couldn’t handle my dad’s ashes even though it strangely didn’t really seem to bother me at all. Yet, I couldn’t handle seeing his picture, which she sought comfort in regularly. Suddenly, a dark silhouette appeared beside me like a ghost. In complete terror, I shrieked and jumped.

My niece had followed me! Not meaning to scare me at all, even though it’s exactly what she did. I had to laugh at the comedic timing.

While my mom was dealing with a cold, Josie didn’t want to leave her side. The word “sick” had now confused her. She thought my mom was going to eventually leave for good like my papa had. My sister had to explain to her that what happened to papa was not the same as having a cold and nana would be fine. When you get sick, you get better eventually. It’s a cruel thing to discover with age that being sick can also mean something else sometimes.

•

My mom and I went back to stay with my sister for a while in north Austin. We would go back and forth, to break up the monotony of being alone in Houston. At least in Austin my mom could be with her grandkids. She refused any offered counseling services but called people on the phone and would break down crying any chance she got. She couldn’t see any redeeming purpose of a counselor nor did she want to acknowledge mental health.

I don’t know if it’s a generational, cultural, or even a religious thing. It’s as if people think they aren’t being strong enough or that they’re doing something wrong if God isn’t enough to keep them happy and stable. Maybe somehow a message got contorted that you can’t believe in both mental health and God simultaneously. Perhaps it’s society’s good old-fashioned desire to judge, be cruel and stigmatize others for what most of the world views as “weakness” admitting to depression or emotional troubles. Whatever it is, it seems to be something deeply ingrained, things people don’t want to admit to.

It seems as though asking for help is like admitting failure. For a large part of my life, I was afraid to ask for help, to admit I was depressed. In my twenties I finally reached out for help with anxiety and depression because things had become dire, it felt as if I was struggling to live every single day. I simply didn’t care about the stigma anymore, all I knew was that I wanted to stay alive. Thankfully that agony is only a memory now. Naturally, I wanted my mom to recognize the importance of counseling and to feel the relief I had, but she didn’t want any part of it. I couldn’t force her to do something she didn’t want to, a process where success hinges on one’s own motivation.

•

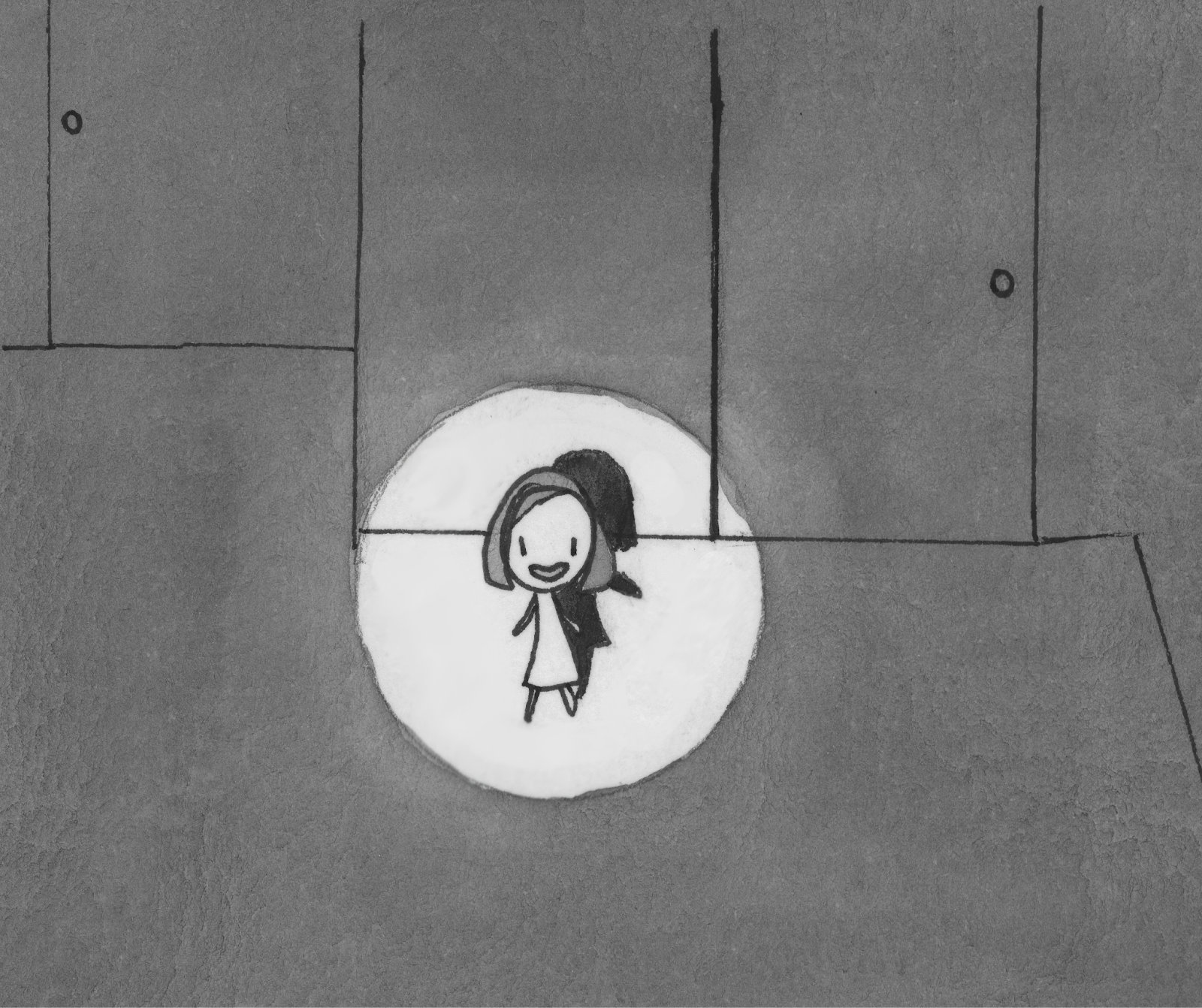

Late one night, I was in my nephew’s room on my computer when I heard a strange sound. It was around two am when I crept out of bed and slowly opened the door. As I inched my way into the dark hallway, I peered over the stairs down to the first floor. There in the dimmed light was my mom and nephew playing volleyball with a balloon, muffling their giggles. Only my mom would do something like this. I was relieved to see them laughing, it made me smile.