In one of the last months of living in our house alone, my mom had a panic attack. I don’t think she realized that’s what it was. Our neighbor came over and made her some lunch while Pam came over and stayed the night. It’s funny how unspoken these things are, no one called it anxiety or panic. I’m glad that there were people who came to help her.

My sister moved my mom out of the house that October. In the process of lifting every literal thing, my sister ended up throwing her back out. It was a horrible conclusion to an already chaotic ending. After the ordeal of what my mom experienced, she didn’t want to be in the house anymore. She also couldn’t drive. The house that we all assumed would be there in our future, was changed. It wasn’t the same. The monster had turned it all into something else. My mom moved in with my sister. I tried not to think of any of it.

One night in bed watching tv, the Oklahoma weatherman showed a massive storm raining down on Houston. The familiar image of Houston, arrows swirling around it, I instantly thought of my house. All my childhood on our tv I saw the same map on our news, while in the comforts of our home. I thought of how our house looked during rain storms. All our plants and trees trembling and swaying. Our home, a dark, empty, mausoleum of nearly 45 years of our life still echoing inside it. A thought I could never have dreamed of existing. Dozens of arrows plunged into my body for our home and life that was now a shadow. All I wanted to do was scream. Jon didn’t understand.

•

During October I had another dream, this time my dad was still sick, as I’d last seen him. He looked at me with such a sad face, almost apologizing wordlessly, as if he realized he was a burden. I woke up upset. The dreams were my only link to him, but it was a stressful link. On another day, I dreamt we sat on the couch together in our old living room, crying and hugging one another as if in some understanding of what we had been through. The dreams continued at a steady pace for a year.

•

Thanksgiving, like Father’s Day, was an effort to avoid any memories. All I could do was to try and not think about our kitchen. My dad in his blue shirt, shorts, flip flops and Astros hat, making his perfect turkey; even though he hated turkey and preferred ham. So there was always ham, along with our special stuffing and gravy. All the familiar and enticing smells floating through the house I can no longer recall. The face of Puddles, looking through the screen door from the backyard that was open, because it was never cold on Thanksgiving in Houston. I tried to not think of any of those things. Sometimes I was successful, sometimes not.

After surviving the fall semester, I would finally be graduating in December 2015. All the education students had a ceremony where we received a certificate and medal for our accomplishment. At my table were classmates of my same major, many faces I hadn’t seen in ages from being off campus for two semesters. While sitting at a giant round table, quickly I noticed one person who looked uncomfortable. I had this person in previous classes, they had always been extra chipper and outgoing. Now everyone altogether, on what should have been a good day, they looked as though they had ants crawling all over them.

I studied them quietly and then tried to make small talk. They said something about having to leave and were concerned about having missed quite a few days of their student teaching. At some point, I asked why and they replied in a high pitched, sardonic version of happy, “Um, well… my dad… he’s dying.” with a flash of anger that I knew quite well. They thought I was an outsider, who hadn’t felt the tragedy that they were now at the mercy of.

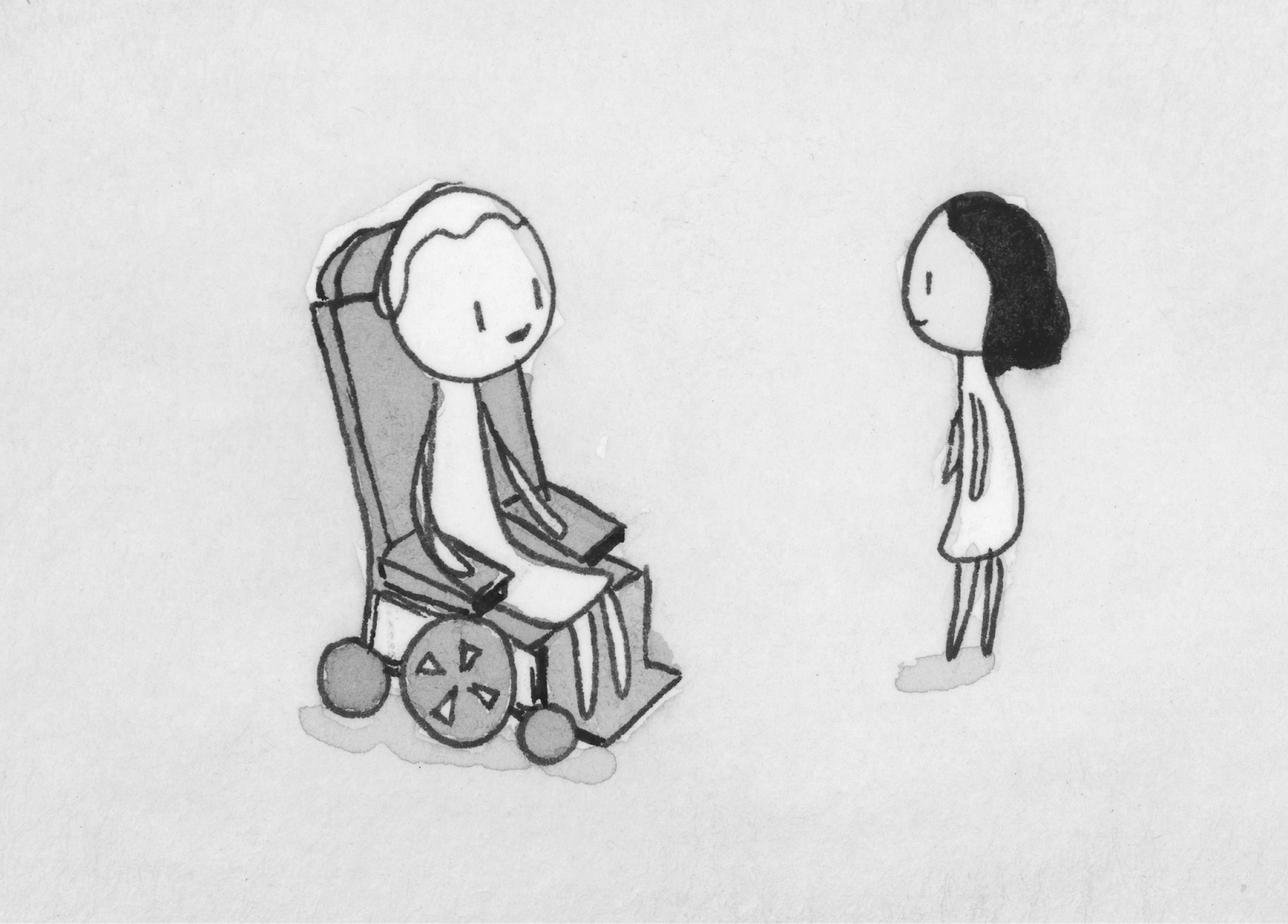

Everyone else at the table seemed to shrink away, but I sat transfixed. I kept staring at this person, wanting to tell them what I had just been through, but I couldn’t find the words. I knew that when I had been in their place, I didn’t want to acknowledge the idea of my dad dying, it hurt too much. I sat there in torture, trying to think of anything, something to say to them. I searched frantically in my mind, wanting badly to say all the things that I would have wanted to hear a year ago, being in that same exact part of their journey.

Watching their anger and flashes of frustration, I knew there was nothing I could say. There were no magical words I could conjure to help. Nothing would help, except someone saying the words “your dad won’t die.” We weren’t close enough for me to go over and say a bunch of heartfelt things without it being weird. I felt despair and failure. I decided to let them be instead of running the risk of making them far more upset, ruining that public veneer that I also remembered well. That person was the “before” and I was the “after” picture. I was the reality they didn’t want to be and I understood. I was still trying to accept it all myself. In my best estimation of that moment, I would have likely caused them only pain.

Also there at the ceremony was the professor whose class I had written the paper about my dad for, two years earlier. The person struggling at my table, had also been in that class with me. The memory of the two of us as younger, happier versions felt so far away. That paper was such a wonderful experience between me and my dad. I was grateful that I had done it. I went over to the professor and told him hello, he remembered me. Then I told him that I was thankful for having done the paper and how my dad had passed away.

He looked sad to hear it and talked about his own dad’s death. “You know what I miss most about my dad? His laugh,” he said with tears in his eyes. I smiled and nodded in agreement. That moment was probably the first time I could talk about my dad dying with ease. It was remarkable progress I never even recognized until writing this.

•

I went to Austin to spend Christmas with my family. It was as difficult as you’d imagine. We were all doing our best to avoid the obvious, and not accomplishing our task. It felt odd. There was a palpable void. It seemed unnatural that my dad wasn’t there. When I went to get forks and spoons out for dinner, there was now an odd number. Every time I counted them before a meal I felt like crying. I didn’t want to imagine what my mom was thinking.

On Christmas eve Jon and I slept in my nephews room, as I had done the months earlier living with my mom. The massive window upstairs in his room faces the street. With the sheer curtains, light easily poured in. In the early hours of Christmas morning, I awoke to a beam so bright it felt like a flashlight being pointed at my face. It was as if the moon were alive, massive and radiating, like the sun. It seemed as though it was desperately trying to look at us through the blinds.

I got up, squinted and walked over to the window. I looked out, it was magnificent. Jon slept, unbothered. I looked wearily into the darkness and considered digging out a camera to take a picture, but then I realized how tired I was. I crawled back into bed, the moon still bathing over us on that early Christmas morning. Part of me still wishes I had taken a picture, in the same way I wish I had answered that mysterious phone call the day after my dad died.

•

January came and there were more hurdles that I wasn’t prepared to deal with. Going through the holidays was already hard enough. I felt myself not wanting to approach the anniversary of his death. It was as if my heels were digging into the ground. I was fighting it. I stayed in bed as I unraveled, for another damn time. I was still full of anger. All of my thoughts were still lodged in the same disbelief, how did this happen?

I didn’t bother watching my favorite movies, listening to my favorite songs or going out because nothing helped. I felt disappointed in myself. The one year anniversary was getting closer and I hadn’t improved as I had hoped or expected to. I actually didn’t have any clear expectations at how I should be recovering from my dad’s death, but I still kept measuring myself in the most negative ways. Which if you’re keeping track with me, makes no sense.

Nearer to Valentines, I found myself becoming hysterical. All I could think about was the previous Valentines. That sad weekend with the heart shaped tin he ate chocolates from. The fast-food trip in his car, feeling guilt and shame for missing Jon and Macchi. I hated thinking of the evening when he took that awful pill that knocked him out for hours and started his path out of this world. The anniversary of his death loomed all around. It was starting to feel like I was being pushed into a doorway that led to nothing, just infinite darkness.

To me, that first year meant I still had a connection to him when he was still living, it didn’t seem so bad when I had that. But now it would be over a year, our final connection would be severed. I was terrified. With each passing day, it felt as though I was being dragged closer to that doorway, some place beyond. What would it mean? How would it feel? I didn’t want to know.

It was hard to decipher if it was me rejecting death or the cruelty of how my dad had been taken off this earth. Maybe it was both. Regardless, I resented and despised the idea that there would ever be a time I could be calm and accepting over his death. For some reason in my mind, I equated finding peace with defeat, as if acceptance meant I had given up on him. It’s hard to explain now when it felt so logical back then. There were times that the exhaustion of being under so much anger made me wonder how I’d ever go on living a normal life. Would I ever be free? I genuinely questioned myself at becoming a traitor for letting go of all that anger. In some ways, it was all I had.