For almost the next two years after my dad died, I had moments of uncontrollable sobbing that were often complete surprises to me. I wondered if it was normal, if anyone else had gone through that. Was it normal to cry that much? Years later I read an article advocating to discontinue the phrase and mentality of “battling” cancer. I immediately understood what they meant. In dozens of the breakdowns I’d experienced, I’d apologize out loud to my dad, repeatedly saying “I’m sorry” and “we tried.”

Making cancer a personal “battle” was a burden that I’d given myself without realizing. It should have never been that way. Making the cancer my battle unknowingly made it my responsibility and therefore, my failure. But cancer can’t always be controlled, as the counselor from Cameroon had tried to warn me. The “battle” mentality took years to undo. I had to learn to view the experience as a journey, even with the ending I didn’t want.

•

I was writing a lot. Part of me kept questioning, why should I forget it all? I considered doing something with everything that I was writing, but I feared sharing such a personal experience. I’ve always been meticulously guarded about anything I’m going through. The idea of letting it out made me uneasy. Still, the conflict inside me grew on how to reconcile the memories, how to “live with it all.” I felt changed, something in me was not quite the same, but not in the sinister way as I had once feared.

Summer came in quickly. In a span of a month, I got married and then got my first real job. All of which I resented deep inside because my dad missed all of it. It was another rapid amount of change occurring. My mom and sister had ordered me a bouquet for my low-key wedding day, in which Jon and I would have a small ceremony with his parents. As I opened the box and took the bouquet out I saw a small silver pendant with a picture of my dad pinned to it. Seeing this, I became angry and upset. I immediately put it away. For a moment, I wondered why my mom and sister would do such a thing. Then after another minute passed, I wondered what the hell was wrong with me.

My life was stuck in one long, awkward phase. I didn’t make enough money to get my own place. Half of my life was in boxes and I had no home of my own. Jon and I were living with his parents trying to make a life as artists. There’s no plan or path that we are supposed to follow. The world is a brutal place if you’re an artist, trying to figure it all out on your own. Nothing was working out the way I’d originally planned. I felt like a total failure. It definitely was not like all the movies and tv shows where people had their professional life and family by 30.

I’d grown cynical. Any spirituality I had was dead and gone. I was set on thinking nothing mattered. I was miserable but constantly wishing I could talk to my dad again. In desperate times when I was alone I would whisper, “Where are you? Where did you go?” Daily I was looking for signs of him and found nothing.

•

July evaporated like rain on a sidewalk and within two weeks I was trying to set up a classroom, attend mandatory meetings, plan lessons and learn about three thousand new things. It was an overload. I tried to not think of my dad anymore around this time in order to avoid the pain. Thoughts of my dad were like an overstuffed closet where I kept throwing things I didn’t know what to do with.

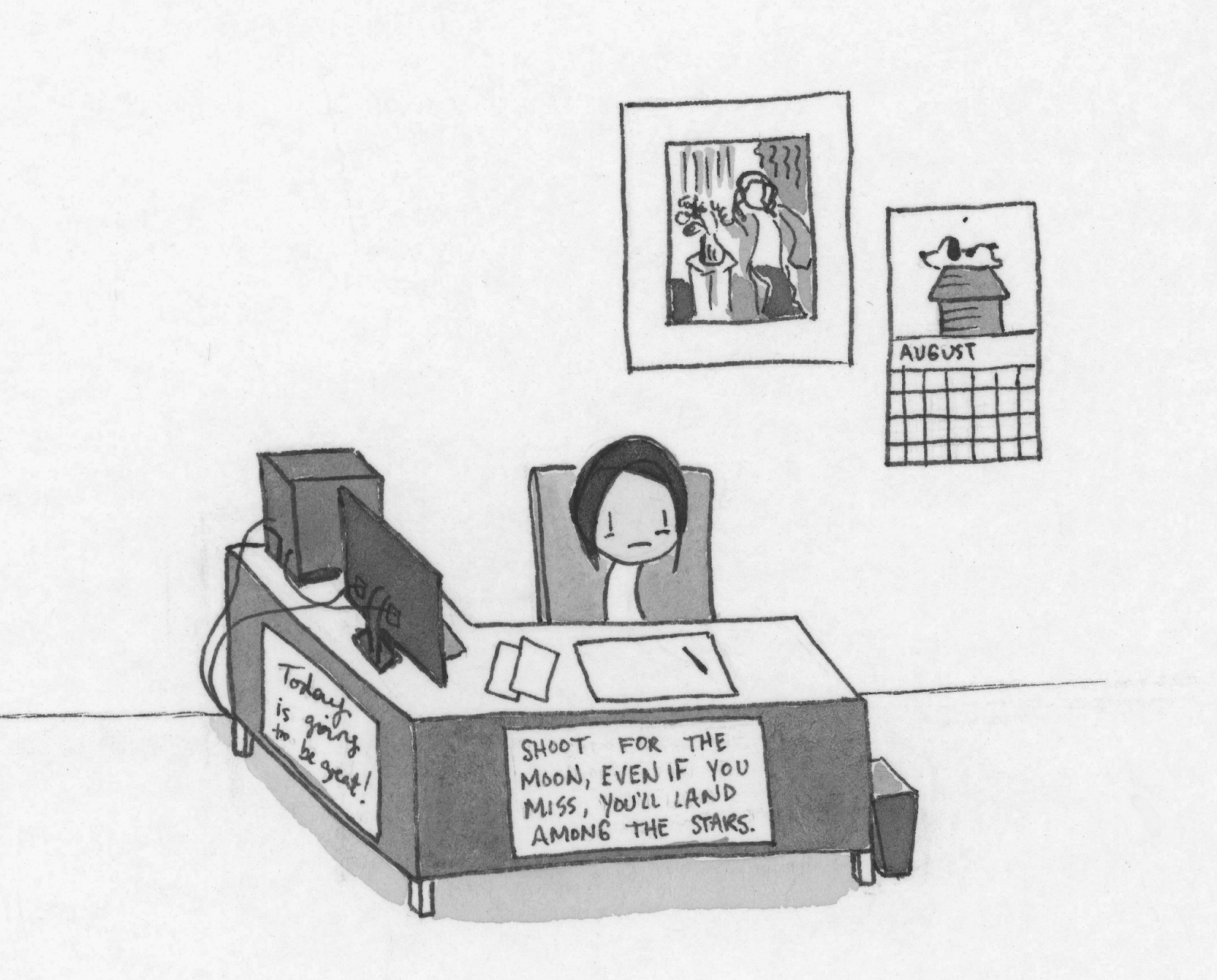

A couple of days before my first day of school, I was completely beaten down, exhausted and depressed at how behind I was on everything. It took forever just to get my room together. I maxed out my credit card just to get new clothes, shoes and decorate my new room so it wouldn’t be empty. I had spent so much time and money trying to make it look nice. Sweaty and tired, I sat down at my desk. Music played on my computer.

In the corner of my eye, I saw a figure enter the room. I looked up and smiled, ready to do my normal adult performance of happiness. I anticipated a fellow teacher to be standing there, but instead I was looking at an empty doorway. Nobody was there. As my brain canceled the hello I was about to deliver to an empty room, “Don’t You Forget About Me” started playing. I sat baffled, my eyes watered.

My dad was the only person I wanted to see more than anybody, to talk to about what I was doing. He would’ve been so psyched about my room, my new job. He was always too overly excited about me getting a job, even terrible, unimportant ones. I could imagine him walking around in amazement, “This is pretty nice!” he’d say. In my mind I could see him vividly, while the song continued playing. I sat there blinking back my pain. It was just a coincidence, that’s all.

•

The first day I walked into the school, I wore a necklace my dad had given me as a child. I never knew he had picked it out for me as I’d had it my whole life. A tiny gold heart, round, with a sateen finish and angled cuts in the middle. As a kid, I was fascinated by the few millimeters of beauty. So naturally, as a child with reckless curiosity, I attempted to test that beauty by biting on it. My four year old canine tooth dented the perfect heart, thankfully only on the back. An impulsive experiment I immediately regretted.

I hadn’t worn that necklace since I was a kid. After my dad died, I found myself desperate for his presence. Upon finding it again, I decided to wear it. It’s the necklace that was in the picture of me, my sister and my dad, that hung in our hallway. The same picture where I saw the reflection of his diminished body on that horrible night he fell.

I was absolutely terrified to start teaching, to start work. To get my confidence, I wore that heart. No matter how scared I was, I had that necklace to give me the hope that somehow my dad was there, guiding me, watching over me, making it bearable. Everyday I wore that necklace and on the few days I forgot it, I felt a mess. In some weird way, I swore I could feel my dad frown, saying, “You don’t need that. You’re doing it all without me.” In my first school picture as a teacher, that tiny gold heart is around my neck.

School was exhausting, more than I had realized or prepared for. With each week, I found myself taking stock in all my trials and tribulations. Each Friday I noticed that I was extremely sad, for what should have been my favorite day of the week. In the past it had been the day I’d usually call home, to talk to my parents and catch up. Ordinarily I’d get advice from my dad, enjoy his humorous anecdotes about work, life and politics. And now, when I had so much to say, he wasn’t there. I had so many things to ask him, so much advice I needed now, more than ever.

Every Friday after school, I sat in my chair with my heart imploding, trying to hold back the tears. Sometimes I was successful but more than usual I failed. I wanted to tell him about my classes, the kids, my frustrations, things that were funny, but I simply couldn’t reach him. Upset one night I told Jon, “I just want to talk to him again!”

•

For the first two years of my dad’s death, I was in a constant loop of traumatic memories. I was stuck in my own destruction, refusing to accept his death in a morbid defiance, preserving the only absurd agency I had left over the entire situation. My only option now was to burn deeply inside my soul, fighting the monster, refusing the reality. In my head it made sense, my anger was justified. I was battling the evil that destroyed my home, life, future and family.

After a while it seemed harder to understand what I was feeling anymore. What was I getting out of it? What was even happening to me? At some point during my second year of suffering I started to see the pattern. The monster kept baiting me into another spiral until I sat alone, defeated. I questioned if the monster was real. Was it in me? Was it something I needed to believe in, to fulfill this angry cycle? Was it something I needed to see to finally move on? To wrap my hands around its throat? It was never going to be there. Nothing was there. I was tired.